It's been a while since I posted an update about my videogame project, Sketchy Maze but I've still been working on it and had released a handful of updates since my last post about v0.7.1 and my game is starting to get interesting. 😉

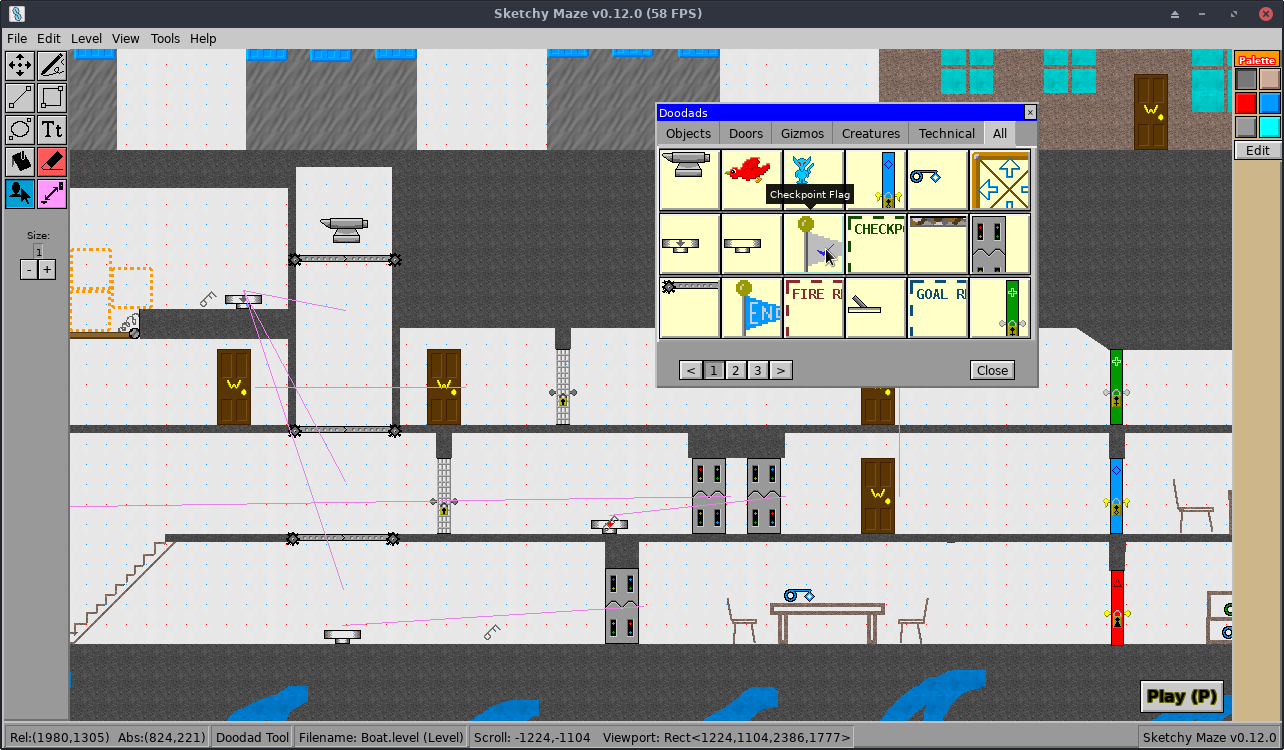

Sketchy Maze is a drawing-based maze game where you can draw your own levels freehand (like MS Paint) and make them look like anything you want. You can draw a castle, a cave or a giant boat, and then play it as a 2D platformer game. You can drag and drop some "doodads" such as buttons, keys, doors and enemies into your level to make it exciting. And as for those doodads? You can also create your own, too, and program them in JavaScript to do whatever you want. The game also includes a built-in Story Mode of example levels to simply play and/or learn from.

Since my last update about v0.7.1 the game has got:

The full change log is always available on the Guidebook for more details.

If you haven't seen my game yet, check it out! It's still in beta so it may be buggy or crash sometimes, but any feedback is welcome!

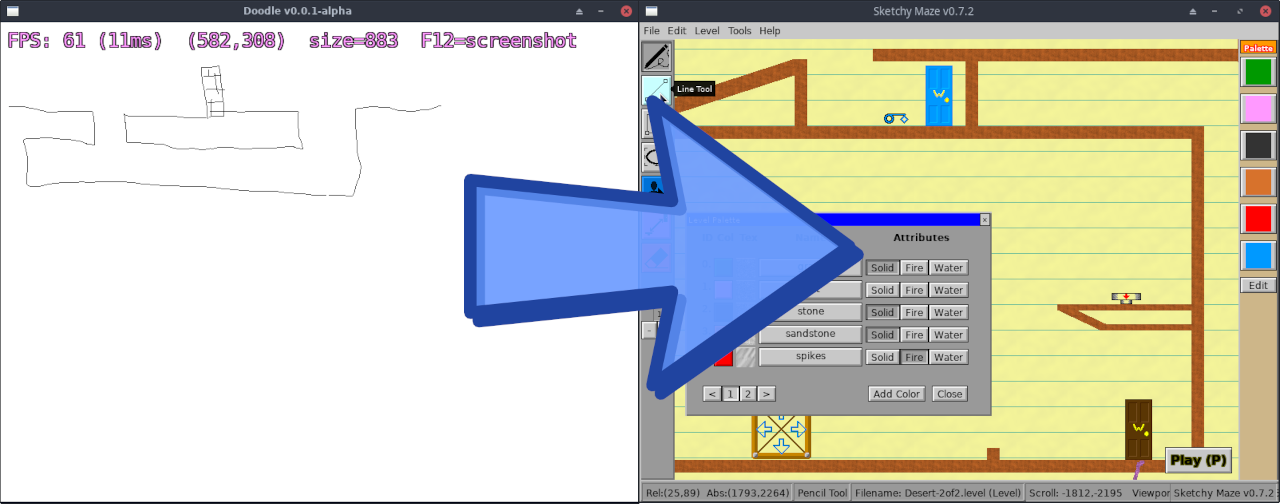

For the past few years, on and off (sometimes more off than on), I've been working on a videogame called Sketchy Maze and had been taking screenshots of it along the way. This blog post will be a bit of a retrospective and a series of screenshots showing it from its very first prototype up to the state that it's in now.

I wasn't even sure I was going to get very far on this project. I had once attempted programming a game in Perl and lost steam after barely having a working prototype. I had dabbled a few times getting started programming a game but then decided my brilliant idea of an RPG game wasn't worth all the programming. Stubbornly, I never wanted to just use a game engine like Unity or Unreal but wanted to program it all myself. And programming from scratch is considerably the harder way to go, so your game idea had better be worth it in the end!

The game idea that won out is a personal and nostalgic one. Back in the 90's when I was growing up with videogames like Sonic the Hedgehog and Super Mario Bros., I would often draw my own "mazes" or levels like on a 2D platformer game, with pencil and paper and then "play" it with my imagination. I'd imagine the player character advancing through my maze, collecting keys that unlock doors, pushing buttons that activate traps somewhere else on the page. I'd write little annotations about which button did what, or draw a dotted line connecting things together. My mazes borrowed all kinds of features from videogames I liked, all your standard platformer stuff: buttons, trapdoors, conveyor belts, slippy steep slopes, spikes and water and whatever I wanted.

So my game concept was basically:

See the full blog post to read how I even got this started and see screenshots of progression between the "Before and After" pictured below. My first target goal was just a stupid simple white window that I can click on to turn pixels black and save it as a PNG image. If I could get that far, I could do all the rest.

Have you ever wondered basically how blockchains work and what it means to "mine a Bitcoin" and why it's a time-consuming (and energy-intensive) process to mine one? In this blog post I'll summarize what basically drives blockchains and how they work, from my understanding of them anyway.

If you're anywhere close to a novice web developer or have ever hashed a password in your life, you already know the basic technology at play here. And even if you haven't, I think I can get you caught up pretty quickly.

The explanation I give below is surely super simplified and is based on my reading of how these work, along with several "Create your own blockchain in under 200 lines of code" type of tutorials which you could find for Python, or JavaScript or anything. It doesn't cover how the decentralized networking aspects work or any of those details, but just the basics on the cryptography side.

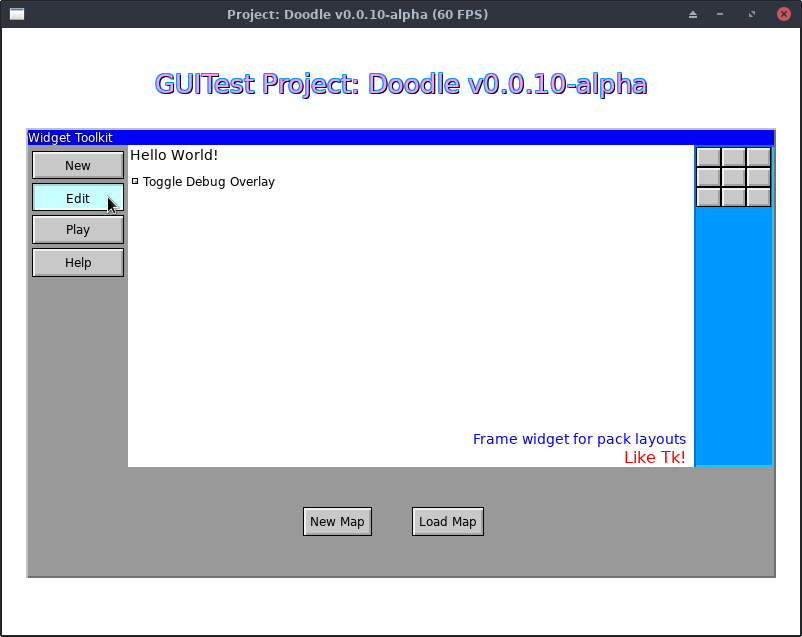

As I've been working on my videogame (codenamed Project: Doodle), I created a few Go libraries that I'm releasing as open source software that can be used to create other, unrelated applications (other games, other kinds of graphical programs, etc.)

These libraries are still in "early development" (meaning I may change their API around a bit as I refactor and add new features) but they are generally stable and I'm good about documenting changes in the code, if you wanna play around with these and aren't afraid of occasional breakages.

This is just a quick blog post letting people know about these libraries. I'll probably post again when these libraries reach a stable "1.0" state, where their API won't change and they'll have a degree of stability guaranteed to them.

I'm generally using GitHub as a mirror for these libraries and will accept issues and pull requests filed on GitHub (I wouldn't expect or want anybody to sign up an account on my local Gitea instance).

I decided early on for my game that I would be using libSDL for my game's graphics, audio, controller inputs and so on -- at least to start out with. I didn't want my game to rely on SDL though: I needed the flexibility to swap it out for OpenGL or Vulkan or Metal or any other back-end driver as needed to expand my game to future platforms.

So I created go/render as a "rendering engine library" for 2D graphics in Go. It presents an API interface for drawing pixels to the screen which can be implemented by various back-end "drivers" that do the real work.

Currently it supports SDL2 for desktop applications (Linux, macOS and Windows) as well as a WebAssembly driver that uses the HTML Canvas API. (I have a build of my game to WebAssembly, but WASM performance is not great yet.) Examples are included in the git repo for both desktop and WASM applications.

My game also required a UI toolkit for easily adding buttons, panels, windows and basic user interface controls to the game.

There were a handful of options I could've gone with: desktop UI toolkits like Gtk+ or Qt could've wrapped around my SDL surface and provided menu bars and button toolbars, but I wanted to minimize my inclusion of C or C++ libraries with my Go application. I was fortunate that go-sdl2 provided clear documentation how to cross-compile my program for Windows, and I didn't wanna push my luck bringing in yet more C libraries that might've made my game harder to ship. This also ruled out some potential SDL2-based C libraries for UI controls as well.

So I created my own UI toolkit in Go, and it uses my go/render library as its

graphics back-end: meaning my UI toolkit can work for SDL2 desktop applications

and as WebAssembly applets.

The library's API is inspired by the Tk GUI toolkit which I had prior experience with in Perl and Python (see my Tk blog posts).

It currently supports widgets such as Labels, Buttons, Checkboxes, Tooltips and (virtual) Windows (with title bars that can be dragged around and closed). The Frame widget allows easy arrangement of child widgets using Tk-style Pack and Place controls.

Future planned widgets include: menus and menu bars, tabbed frames, text input boxes, scrollbars and sliders (in roughly that order).

The newest library implements a simple audio engine for playing music and sound effects. My game needed these, and doesn't have any fancy requirements yet, so this library provides the basics for loading music (.mp3 and .ogg) and sounds (.wav) and playing, pausing and stopping them.

Currently it only supports the SDL2 (Mixer) driver. This module is independent

from go/render and you can mix and match (or not) that library.

Future planned features include: adding WebAssembly support (Web Audio API), maybe branch out to other back-end drivers as needed.

In this blog post, I'll recount my experience in web development over the last 20 years and how the technology has evolved over time. From my early days of just writing plain old HTML pages, then adding JavaScript to those pages, before moving on to server-side scripts with Perl (CGI, FastCGI and mod_perl), and finally to modern back-end languages like Python, Go and Node.js.

Note that this primarily focused on the back-end side of things, and won't cover all the craziness that has evolved in the front-end space (leading up to React.js, Vue, Webpack, and so on). Plenty has been said elsewhere on the Internet about the evolution of front-end development.

I first started writing websites when I was twelve years old back around the year 1999. HTML 4.0 was a brand new specification and the common back-end languages at the time were Perl, PHP, Coldfusion and Apache Server Side Includes.

I was discussing passwords with someone recently and thought of a neat little hands-on exercise that shows not only how password hashing works, but shows you a real-world example of cracking a weakly hashed password just using Google.

The hands-on exercise should be easily approachable for beginners. I'll also go over a general history of passwords on the Internet -- I've been working as a web developer long enough to watch the whole transition from MD5 to bcrypt play out.

Any Unix-like environment with the md5sum command. Most Linux distros have it

by default as part of the coreutils package. The Windows Subsystem for Linux

might work.

Mac OS might have these built-in too. Not sure.

Or just find a program that can generate MD5 hashes for you, preferably as a downloadable program you run on your computer, or one that runs from a web page but in JavaScript and without the server being involved.

The Internet is full of freely available source code. If you're a software engineer and you're writing a new application, chances are a lot of the code you're writing has already been written thousands of times before by other engineers that came before you.

Some engineers seem to believe you can compose an entire complicated app just by mixing and matching tiny pieces already written before you. Pull a session manager from here, a template engine from there... a login manager, a password manager, a database accessor... all of these being small off-the-shelf components that you're trying to duct tape together into one coherent app. The actual code you as a developer write is just the few lines needed to stitch these all together. You'll have a production-ready app running in just a few minutes!

Sure, but in my career as a software engineer I've learned that it's usually better to write all those pieces yourself so that they fit together perfectly how you want, not just "good enough."

This is a story of a particularly annoying Python module I was dealing with at work.

This is something I wanted to rant about for a while: event loops in programming.

This post is specifically talking about programming languages that don't have their own built-in async model, and instead left it up to the community to create their own event loop modules instead. And how most of those modules don't get along well with the others.

0.0130s.