Somebody had asked me about this recently, and I thought I must have already written a blog post about it before, but apparently I had not!

If you (or someone you know) has been curious about how to break in to software engineering as a career (or a career change), then this post is for you. A proper college degree is NOT even necessary for most software jobs!

The basic steps I will recommend are as follows:

Now I'll go into each of these in more detail.

For my career, I have mainly worked in the "web development" space so my recommendations here are coming from that world. See the footnotes for some advice for other software development paths (e.g. videogame development).

If you don't know any programming languages yet, you should choose a popular language to be your first one, and you should prefer to choose one which has a large amount of companies that use it because that's where the jobs are at.

My current recommendations would be:

If you aren't familiar with what front-end vs. back-end is, I can describe them briefly:

It's also possible to be a "full stack developer" where you are building both back-end and front-end code, but that usually requires you to learn multiple programming languages and technology stacks. For somebody just getting started, your time would be better served to pick the one you resonate with the most and focus your attention on learning the programming languages and frameworks for that language.

Note: after you've learned one language, it is much easier to learn your second one. There are so many things they all have in common: functions, variables, and control flow are very similar across them all.

There are tons of free tutorials online that teach you how to build web apps in any of these programming languages. Just google for something like, "Build a web blog in Python" or "Build a Twitter clone in JavaScript".

Those two projects (a web blog and a Twitter clone) are very common examples that you'll find a tutorial for in any programming language. "To Do" apps are another example. These kind of projects will have you learning many real world skills, such as databases and authentication cookies, that you would use at a real job.

Most such tutorials will not only help you learn the programming language itself, but also use a popular "web framework library" built for that language. Almost nobody is programming a raw HTTP server in Python, but they will use a web framework that provides the basic structure and shape of their app and then they fill in their custom business logic on top.

For some specific recommendations of very relevant frameworks that currently see widespread use in business:

In my career at Python shops, we've always used Flask to build our apps and Vue.js has been most commonly used on front-ends at multiple companies I've worked. React.js is very popular as well.

If you aren't disciplined enough to teach yourself how to code, and you don't want to dedicate two to four years of going to University, you can look for some "coding bootcamps" in your area too. Those bootcamps will typically go for several weeks and teach you everything you need to know about web development.

I've interviewed and worked with people whose sole educational experience was via these bootcamps and they did just great on the job.

A very good way to learn a programming language is to actually have a project that you want to build.

If you just go to a programming language's website and read through the tutorials there, they can be rather boring. They have you writing trivial little programs to learn how if/else expressions work, and silly things like that. After you have picked up the bare basics, I recommend jumping in and starting on a project of your own.

That's where the aforementioned "build a blog" style of tutorial will come in. Those will give you a good structure to follow, using real world frameworks and libraries that professional developers use at work.

It doesn't really matter much what you choose for your project. If you don't already have a website, programming a web blog is a good first option. Then, you'll have a website that you can post things on and document your journey of learning how to be a better programmer!

You could also build something like a videogame, or a chatbot, or a little web page that connects to various social media APIs and provides status updates from all your friends in one place. Something to scratch your own itch. It doesn't really matter a whole lot what your project is!

The important part, though, is that you open source your project and get a GitHub account and put your source code on it for others to see. (If you don't like GitHub, you can try GitLab instead).

The point is: having source code online will already make you stand out from the crowd when you begin applying at places to work. I have interviewed hundreds of developers over the course of my career, and most of them don't have a GitHub link or anything on their resume. Those who do are already putting themselves off to a good start with me.

After you have gotten a project or two under your belt and have learned the basics of how to build a website, you can start applying to companies for a web developer position.

There are always a ton of little startup companies or other small businesses who need anybody that can code. They don't even care if you have a college degree or not, and that is where having some source code up on GitHub can be helpful, so you can point to that as evidence that you know how to code.

The larger corporations will often say they want their candidates to have a Bachelor's degree in Computer Science or similar, but, once you've gotten your foot in the door at a small startup company and keep at it for about 5 or 10 years, you'll start getting recruiter e-mails from even Google, Meta and Amazon with them wanting you to apply to them. A few years of "real world" experience is typically a lot more important than some piece of paper from a university.

The above was basically how I did it, and I'll tell you how.

I taught myself how to program since I was a young teenager. I learned how to write web pages in HTML when I was 12 (using the very same W3 Schools HTML tutorial that I linked above!), JavaScript soon after, and when I was 14 I taught myself Perl so that I could program chatbots for AOL Instant Messenger.

Throughout my teen years, I had published many Perl modules online as open source software. Some were related to my chatbot projects, some of them were Perl/Tk GUI toolkit modules, some were very niche things such as Data::ChipsChallenge which could manipulate data files for the old Windows 3.1 game "Chip's Challenge".

I got my first proper job as a software developer purely because of my open source projects. I just pointed at my CPAN page as a place for recruiters to see my work.

For my second software development job (because I was still fairly green with only a few years' experience), the job interview consisted 100% of me going through the source code of RiveScript.pm, my chatbot project I had written in Perl, and explain how I designed my code and what I would do better if I rewrote it all again.

And: nobody ever asked me about a college degree for any of these jobs. When I got my first job, I was only one year in to a college program (at ITT Technical Institute, rest in peace). I only even went to college because motivational speakers at my high school made me think it was absolutely required. I only finished out my Associate's degree (two years total) and called it quits, only because I wanted to have something to show for my student loan debt at least. But nobody in my entire career has ever asked or wanted to verify my college degree.

Way back when I was interviewing to get my first couple of software dev jobs, I was naturally pretty anxious and worried that I wouldn't do well enough to pass those interviews. But after I got in and then it was my turn to conduct the interviews, and got to see how it looks from the other side of the table, I wonder what I was ever so worried about.

Throughout my career, I have interviewed hundreds of software developers. Many of them were fresh college graduates who went to school for computer science, but had no "real world" coding experience. Others had come from other companies and had years or decades of experience.

A thing that surprised me is that so many people who come in for an interview, just don't know how to program. I once saw this article, "Why Can't Programmers... Program?", which may be the origin story of the "Fizz Buzz" meme of recent decades.

But, I've found it to be fairly accurate. At a software dev interview, we'd often ask the candidate to write out a quick "puzzle program" to test their logic and coding ability, and for most candidates, it was like pulling teeth. They would usually get through it, with some help, over the span of 20 minutes or so.

Usually, it was the fresh college graduates who struggle the most. You'd think, being fresh out of school, their knowledge of programming would be sharp. But, in class they learned a lot of esoteric problems and rote memorization of algorithms, so when faced with a new problem they haven't specifically seen and practiced before, they freeze. Whereas programmers who had a whole career already of real world experience at various companies, they fared a lot better on these kind of questions.

The point I'm wanting to make is: if you actually know how to program, even if you're nervous at the interview, it is a night and day difference and you will already stand out greatly compared to most of the candidates who walk through that door. Having your own "real world" projects you programmed for fun, and put on GitHub, puts you at a great advantage even above the fresh college graduates who spent the last 4 years learning about computers.

When I see a GitHub link on someone's resume, it's a huge green flag for me. In the time leading up to the interview, I'll check out their source code and prepare some questions about it. If you can walk me through your projects and explain how they work, you're basically going to pass the interview. It may not seem like much, but you would be a breath of fresh air for the interviewer after they just watched the 10 previous candidates struggle their way through a "Fizz Buzz" algorithm.

This one is a valid question and the answer is just that "we don't know."

The above advice all worked out great for me and others I met during my career. The software industry bubble may be finally about to pop soon. The industry is genuinely concerned that "junior developers" may start to go extinct, as companies race to replace them with A.I. and only retain their "senior developers" on salary. Eventually, those senior developers will retire or die off, and nobody will know how to code anymore because A.I. has made everyone dumb and companies won't be able to hire new senior developers to replace them.

However: I say learning how to program is a valuable skill to have no matter what you do for your career. Even if you don't get a job as a software developer, being able to write little scripts and programs to automate the tedious parts of your job will continue to pay dividends for your entire lifetime.

While the above advice was especially for "web development" jobs, much of it applies more broadly to any kind of software development.

If you want to get into videogame development for example, C Sharp (C#) is a useful language to learn because of its prominence in the popular game engine Unity. Those are also useful skills if you want to program Virtual Reality (VR) applications.

If you are interested in mobile apps, the answer is straightforward there: Swift for iOS and Kotlin for Android, and there are many mobile app tutorials out there to get you started.

If you want to get into "systems programming" such as to work with microcontrollers and embedded systems, C is still king and will never be going away, and Rust is a popular up-and-coming language with many new jobs opening up as it can fulfill many of the same roles that C can, but in a more (memory) safe way. Many companies are rewriting their systems in Rust lately, and Rust has a massive library of modules available for doing anything from web development to videogames to desktop/mobile applications to embedded systems development.

And the rest of my advice above still applies: pick a language, check the job market if that's a concern, and then pick a project.

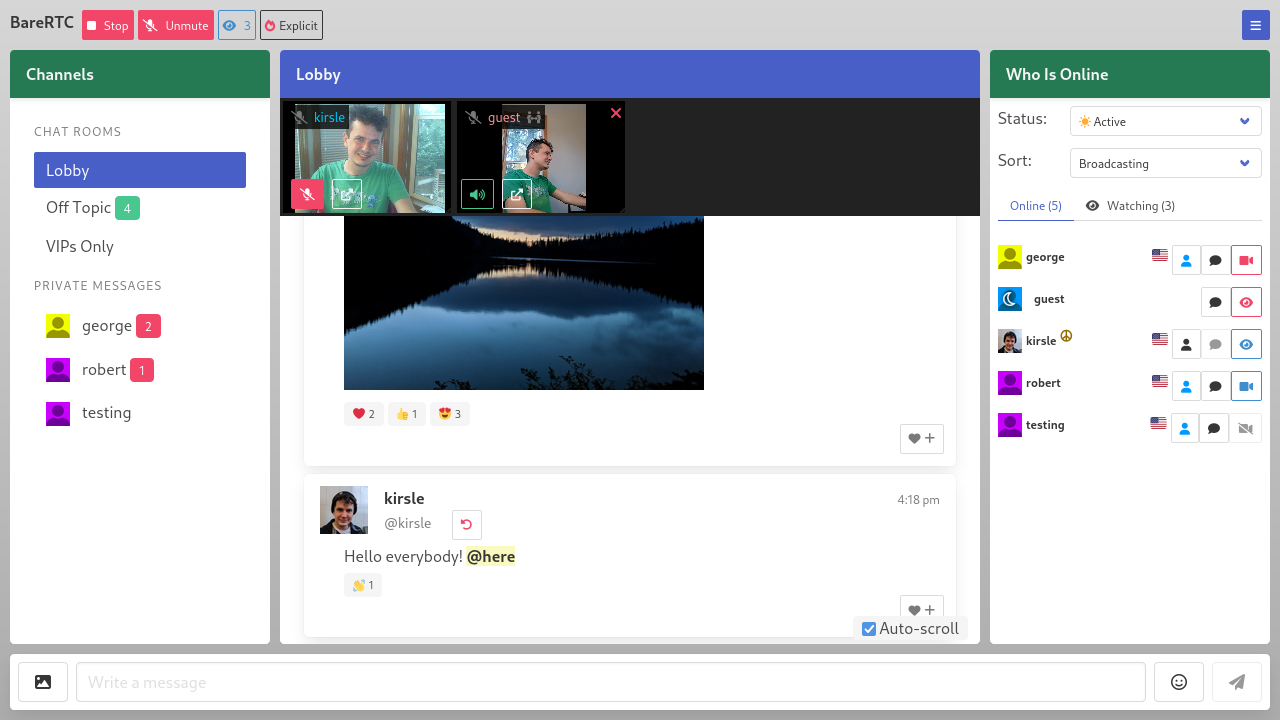

A while back (February 2023) I built an open source webcam chat room for one of my side project websites.

It was very much designed to resemble those classic, old school Adobe Flash based webcam chat rooms: where it is first and foremost a text based chat (with public channels and private messages), and where some people could go on webcam and they could be watched by other people in the chat room, in an asynchronous manner.

It didn't take terribly long to get the chat room basically up and running, and working well, for browsers such as Chrome and Firefox - but it was a whole other story to get it to work as well for Apple's web browsers: Safari, and iPads and iPhones.

This blog post will recount the last ~year and change of efforts to get Safari to behave nicely with my chat room, and the challenges faced and lessons learned along the way.

First, it will be helpful to describe the basic features of the chat room and how I designed it to work, to set some context to the Safari specific challenges I faced along the way.

There are a few other features on top of these, but the above are the basic fundamentals that are relevant to this story about getting this all to work on Safari.

The additional features include:

The underlying web browser standard that allows videos to be shared at all is called WebRTC, which stands for "Web Real Time Communication." It is supported in all major web browsers, including Safari, but the devil is in the details.

WebRTC basically enables two web browsers to connect to each other, directly peer-to-peer, and exchange data (usually, video and audio data but any kind of data is possible). It can get two browsers to connect even when both sides of the connection are behind firewalls or behind a NAT (as 99% of regular home Internet users are).

For my chat room, it means that webcam data is sent directly between the chat users and none of it needs to pass through my server (which could be expensive for me to pay for all that bandwidth!).

It's a rather complex, and poorly documented, system but for the sake of this blog post, I will try and distill it down to its bare essence. The following is massively simplified, but if curious to dive in to the weeds on it, the best resource I found online is this free e-book: WebRTC for the Curious.

When two users are logged on to my chat room, and one wants to open the other's camera, the basic ingredients that make the WebRTC magic work includes:

The signaling server in WebRTC is much simpler than it sounds: it is really just any server you write which is capable of passing messages along, back and forth between the two parties who want to connect. It could be a WebSocket server, it could be based on AJAX requests to a PHP script, it could even be printed out on a post card and delivered by snail mail (though that way would take the longest).

For my chat room's use case, I already had a signaling server to use: my WebSockets server that drives the rest of the chat room.

The server side of the chat room was a WebSockets server, where users would post their chat messages and the server would broadcast those back out to everybody else, and the server would push "Who's Online" list updates, etc. - so I just added support for this same WebSockets server to allow forwarding WebRTC negotiation messages between the two users.

There are a couple of important terms used in WebRTC that are not super intuitive at first glance.

The two parties of a WebRTC connection are named the Offerer and the Answerer.

Both the Offerer and the Answerer are able to attach data channels to their side of the connection. Most obviously, the Answerer will attach their active webcam feed to the connection, so that the Offerer (who wanted to watch it) is able to receive it and show it on their screen.

The Offerer is also able to attach their own camera to that opening connection, as well, and their video data will be received automatically on the Answerer's side once the connection is established. But, more on that below.

So, going back to the original design goals of my chat room above, I wanted video sharing to be "asynchronous": it must be possible for Alice, who is not sharing her video, to be able to watch Bob's video in a one-directional manner.

The first interesting thing I learned about WebRTC was that this initially was not working!

So the conundrum at first, was this: I wanted Alice to be able to receive video, without sharing her own video.

I found that I could do this by setting these parameters on the initial offer that she creates:

pc.createOffer({

offerToReceiveVideo: true,

offerToReceiveAudio: true,

});

Then Alice will offer to receive video/audio channels despite not sharing any herself, and this worked OK.

But, I came to find out that this did not work with Safari, but only for Chrome and Firefox!

I learned that there were actually two major iterations of the WebRTC API, and the above hack was only supported by the old, legacy version. Chrome and Firefox were there for that version, so they still support the legacy option, but Safari came later to the game and Safari only implemented the modern WebRTC API, which caused me some problems that I'll get into below.

So, in February 2023 I officially launched my chat room and it worked perfectly on Firefox, Google Chrome, and every other Chromium based browser in the world (such as MS Edge, Opera, Brave, etc.) - asynchronous webcam connections were working fine, people were able to watch a webcam without needing to share a webcam, because Firefox and Chromium supported the legacy WebRTC API where the above findings were all supported and working well.

But then, there was Safari.

Safari showed a handful of weird quirks, differences and limitations compared to Chrome and Firefox, and the worst part about trying to debug any of this, was that I did not own any Apple device on which I could test Safari and see about getting it to work. All I could do was read online (WebRTC stuff is poorly documented, and there's a lot of inaccurate and outdated information online), blindly try a couple of things, and ask some of my Apple-using friends to test once in a while to see if anything worked.

Slowly, I made some progress here and there and I'll describe what I found.

The first problem with Safari wasn't even about WebRTC yet! Safari did not like my WebSockets server for my chat room.

What I saw when a Safari user tried to connect was: they would connect to the WebSockets server, send their "has entered the room" message, and the chat server would send Safari all the welcome messages (listing the rules of the chat room, etc.), and it would send Safari the "Who's Online" list of current chatters, and... Safari would immediately close the connection and disconnect.

Only to try and reconnect a few seconds later (since the chat web page was programmed to retry the connection a few times). The rest of the chatters online would see the Safari user join/leave, join/leave, join/leave before their chat page gave up trying to connect.

The resolution to this problem turned out to be: Safari did not support compression for WebSockets. The WebSockets library I was using had compression enabled by default. Through some experimentation, I found that if I removed all the server welcome messages and needless "spam", that Safari was able to connect and stay logged on -- however, if I sent a 'long' chat message (of only 500 characters or so), it would cause Safari to disconnect.

The root cause came down to: Safari didn't support WebSocket compression, so I needed to disable compression and then Safari could log on and hang out fine.

So, finally on to the WebRTC parts.

Safari browsers were able to log on to chat now, but the WebRTC stuff simply was not working at all. The Safari user was able to activate their webcam, and they could see their own local video feed on their page, but this part didn't involve WebRTC yet (it was just the Web Media API, accessing their webcam and displaying it in a <video> element on the page). But in my chat room, the Safari user was able to tell the server: "my webcam is on!", and other users would see a clickable video button on the Who List, but when they tried to connect to watch it, nothing happened.

So, as touched on above, WebRTC is an old standard and it had actually gone through two major revisions. Chrome and Firefox were there for both, and they continue to support both versions, but Safari was newer to the game and they only implemented the modern version.

The biggest difference between the old and new API is that functions changed from "callback based" into "promise based", e.g.:

// Old API would have callback functions sent as parameters

pc.setLocalDescription(description, onSuccess, onFailure);

// New API moved to use Promises (".then functions") instead of callback functions

pc.setLocalDescription(description).then(onSuccess).catch(onFailure);

The WebRTC stuff for Safari wasn't working because I needed to change these function calls to be Promise-based instead of the legacy callback function style.

By updating to the modern WebRTC API, Safari browsers could sometimes get cameras to connect, but only under some very precise circumstances:

This was rather inconvenient and confusing to users, though: the Safari user was never able to passively watch somebody else's camera without their own camera being on, but even when they turned their camera on first, they could only open about half of the other cameras on chat (only the users who wanted to auto-open Safari's camera in return).

This was due to a couple of fundamental issues:

offerToReceiveVideo: true option), which Safari did not support.

For a while, this was the status quo. Users on an iPad or iPhone were encouraged to try switching to a laptop or desktop PC and to use a browser other than Safari if they could.

There was another bug on my chat room at this point, too: the Safari browser had to be the one to initiate the WebRTC connection for anything to work at all. If somebody else were to click to view Safari's camera, nothing would happen and the connection attempt would time out and show an error.

This one, I found out later, was due to the same "callback-based vs. promise-based" API for WebRTC: I had missed a spot before! The code path where Safari is the answerer and it tries to respond with its SDP message was using the legacy API and so wasn't doing anything, and not giving any error messages to the console either!

At this stage, I still had no access to an Apple device to actually test on, so the best I could do was read outdated and inaccurate information online. It seems the subset of software developers who actually work with WebRTC at this low of a level are exceedingly rare (and are all employed by large shops like Zoom who make heavy use of this stuff).

I had found this amazing resource called Guide to WebRTC with Safari in the Wild which documented a lot of Safari's unique quirks regarding WebRTC.

A point I read there was that Safari only supported two-way video calls, where both sides of the connection are needing to exchange video. I thought this would be a hard blocker for me, at the end of the day, and would fly in the face of my "asynchronous webcam support" I wanted of my chat room.

So the above quirky limitations: where Safari needed to have its own camera running, and it needed to attach it on the outgoing WebRTC offer, seemed to be unmoveable truths that I would have to just live with.

And indeed: since Safari didn't support offerToReceiveVideo: true to set up a receive-only video channel, and there was no documentation on what the modern alternative to that option should be, this was seeming to be the case.

But, it turned out even that was outdated misinformation!

Seeing what Safari's limitations appeared to be, in my chat room I attempted a sort of hack, that I called "Apple compatibility mode".

It seemed that the only way Safari could receive video, was to offer its own video on the WebRTC connection. But I wanted Safari to at least, be able to passively watch somebody's camera without needing to send its own video to them too. But if Safari pushed its video on the connection, it would auto-open on the other person's screen!

My hacky solution was to do this:

But, this is obviously wasteful of everyone's bandwidth, to have Safari stream video out that is just being ignored. So the chat room would only enable this behavior if it detected you were using a Safari browser, or were on an iPad or iPhone, so at least not everybody was sending video wastefully all the time.

Recently, I broke my old laptop on accident when I spilled a full cup of coffee over its keyboard, and when weighing my options for a replacement PC, I decided to go with a modern Macbook Air with the Apple Silicon M3 chip.

It's my first Apple device in a very long time, and I figured I would have some valid use cases for it now:

The first bug that I root caused and fixed was the one I mentioned just above: when somebody else was trying to connect in to Safari, it wasn't responding. With that bug resolved, I was getting 99% to where I wanted to be with Safari support on my chat room:

The only remaining, unfortunate limitation was: the Safari user always had to have its local webcam shared before it could connect in any direction, because I still didn't know how to set up a receive-only video connection without offering up a video to begin with. This was the last unique quirk that didn't apply to Firefox or Chrome users on chat.

So, the other day I sat down to properly debug this and get it all working.

I had to find this out from a thorough Google search and landing on a Reddit comment thread where somebody was asking about this question: since the offerToReceiveVideo option was removed from the legacy API and no alternative is documented in the new API, how do you get the WebRTC offerer to request video channels be opened without attaching a video itself?

It turns out the solution is to add what are called "receive-only transceiver" channels to your WebRTC offer.

// So instead of calling addTrack() and attaching a local video:

stream.getTracks().forEach(track => {

pc.addTrack(track);

});

// You instead add receive-only transceivers:

pc.addTransceiver('video', { direction: 'recvonly' });

pc.addTransceiver('audio', { direction: 'recvonly' });

And now: Safari, while not sharing its own video, is able to open somebody else's camera and receive video in a receive-only fashion!

At this point, Safari browsers were behaving perfectly well like Chrome and Firefox were. I also no longer needed that "Apple compatibility mode" hack I mentioned earlier: Safari doesn't need to superfluously force its own video to be sent on the offer, since it can attach a receive-only transciever instead and receive your video normally.

There were really only two quirks about Safari at the end of the day:

And that second bit ties into the first: the only way I knew initially to get a receive-only video connection was to use the legacy offerToReceiveVideo option which isn't supported in the new API.

And even in Mozilla's MDN docs about createOffer, they point out that offerToReceiveVideo is deprecated but they don't tell you what the new solution is!

One of the more annoying aspects of this Safari problem had been, that iPad and iPhone users have no choice in their web browser engine.

For every other device, I can tell people: switch to Chrome or Firefox, and the chat works perfectly and webcams connect fine! But this advice doesn't apply to iPads and iPhones, because on iOS, Apple requires that every mobile web browser is actually just Safari under the hood. Chrome and Firefox for iPad are just custom skins around Safari, and they share all its same quirks.

And this is fundamentally because Apple is scared shitless about Progressive Web Apps and how they might compete with their native App Store. Apple makes sure that Safari has limited support for PWAs, and they do not want Google or Mozilla to come along and do it better than them, either. So they enforce that every web browser for iPad or iPhone must use the Safari engine under the hood.

Recently, the EU is putting pressure on Apple about this, and will be forcing them to allow competing web browser engines on their platform (as well as allowing for third-party app stores, and sideloading of apps). I was hopeful that this meant I could just wait this problem out: eventually, Chrome and Firefox can bring their proper engines to iPad and I can tell my users to just switch browsers.

But, Apple isn't going peacefully with this and they'll be playing games with the EU, like: third-party app stores and sideloading will be available only to EU citizens but not the rest of the world. And, if Apple will be forced to allow Chrome and Firefox on, Apple is more keen to take away Progressive Web App support entirely from their platform: they don't want a better browser to out-compete them, so they'd rather cripple their own PWA support and make sure nobody can do so. It seems they may have walked back that decision, but this story is still unfolding so we'll see how it goes.

At any rate: since I figured out Safari's flavor of WebRTC and got it all working anyway, this part of it is a moot point, but I include this section of the post because it was very relevant to my ordeal of the past year or so working on this problem.

Early on with this ordeal, I was thinking that Safari's implementation of WebRTC was quirky and contrarian just because they had different goals or ideas about WebRTC. For example, the seeming "two-way video calls only" requirement appeared to me like a lack of imagination on Apple's part: like they only envisioned FaceTime style, one-on-one video calls (or maybe group calls, Zoom style, where every camera is enabled), and that use cases such as receive-only or send-only video channels were just not supported for unknowable reasons.

But, having gotten to the bottom of it, it turns out that actually Safari was following the upstream WebRTC standard to a tee. They weren't there for the legacy WebRTC API like Firefox and Chrome were, so they had never implemented the legacy API; by the time Safari got on board, the modern API was out and that's what they went with.

The rest of it came down to my own lack of understanding combined with loads of outdated misinformation online about this stuff!

Safari's lack of compression support for WebSockets, however, I still hold against them for now. 😉

If you ever have the misfortune one day to work with WebRTC at a low level like I have, here are a couple of the best resources I had found along the way:

Anonymous asks:

What is your favorite memory of Bot-Depot?

Oh, that's a name I haven't heard in a long time! I have many fond memories of Bot-Depot but one immediately jumped to mind which I'll write about below.

For some context for others: Bot-Depot was a forum site about chatbots that was most active somewhere in the range of the year 2002-08 or so, during what (I call) the "first wave of chatbots" (it was the first wave I lived through, anyway) - there was an active community of botmasters writing chatbots for the likes of AOL Instant Messenger, MSN Messenger, Yahoo! Messenger, and similar apps around that time (also ICQ, IRC, and anything else we could connect a bot to). The "second wave" was when Facebook Messenger, Microsoft Bot Platform, and so on came and left around the year 2016 or so.

My favorite memory about Bot-Depot was in how collaborative and innovative everyone was there: several of us had our own open source chatbot projects, which we'd release on the forum for others to download and use, and we'd learn from each other's code and make better and bigger chatbot programs. Some of my old chatbots have their code available at https://github.com/aichaos/graveyard, with the Juggernaut and Leviathan bots being some of my biggest that were written at the height of the Bot-Depot craze. Many of those programs aren't very useful anymore, since all the instant messengers they connected to no longer exist, and hence I put them up on a git repo named "graveyard" for "where chatbots from 2004 go to die" to archive their code but not forget these projects.

Most of the bots on Bot-Depot were written in Perl, and one particular chatbot I found interesting (and learned a "mind blowing" trick I could apply to my own bots) was a program called Andromeda written by Eric256, because it laid down a really cool pattern for how we could better collaborate on "plugins" or "commands" for our bots.

Many of the Bot-Depot bots would use some kind of general reply engine (like my RiveScript), and they'd also have "commands" like you could type /weather or /jokes in a message and it would run some custom bit of Perl code to do something useful separately from the regular reply engine. Before Andromeda gave us a better idea how to manage these, commands were a little tedious to manage: we'd often put a /help or /menu command in our bots, where we'd manually write a list of commands to let the users know what's available, and if we added a new command we'd have to update our /help command to mention it there.

Perl is a dynamic language that can import new Perl code at runtime, so we'd usually have a "commands" folder on disk, and the bot would look in that folder and require() everything in there when it starts up, so adding a new command was as easy as dropping a new .pl file in that folder; but if we forgot to update the /help command, users wouldn't know about the new command. Most of the time, when you write a Perl module that you expect to be imported, you would end the module with a line of code like this:

1;

And that's because: in Perl when you write a statement like require "./commands/help.pl"; Perl would load that code and expect the final statement of that code to be something truthy; if you forgot the "1;" at the end, Perl would throw an error saying it couldn't import the module because it didn't end in a truthy statement. So me and many others thought of the "1;" as just standard required boilerplate that you always needed when you want to import Perl modules into your program.

What the Andromeda bot showed us, though, is that you can use other 'truthy' objects in place of the "1;" and the calling program can get the value out of require(). So, Andromeda set down a pattern of having "self-documenting commands" where your command script might look something like:

# The command function itself, e.g. for a "/random 100" command that would

# generate a random number between 0 and 100.

sub random {

my ($bot, $username, $message) = @_;

my $result = int(rand($message));

return "Your random number is: $result";

}

# Normally, the "1;" would go here so the script can be imported, but instead

# of the "1;" you could return a hash map that describes this command:

{

command => "/random",

usage => "/random [number]",

example => "/random 100",

description => "Pick a random number between 0 and the number you provide.",

author => "Kirsle",

};

The chatbot program, then, when it imports your folder full of commands, it would collect these self-documenting objects from the require statements, like

# A hash map of commands to their descriptions

my %commands = ();

# Load all the command scripts from disk

foreach my $filename (<./commands/*.pl>) {

my $info = require $filename;

# Store their descriptions related to the command itself

$commands{ $info->{'command'} } = $info;

}

And: now your /help or /menu command could be written to be dynamic, having it loop over all the loaded commands and automatically come up with the list of commands (with examples and descriptions) for the user. Then: to add a new command to your bot, all you do is drop the .pl file into the right folder and restart your bot and your /help command automatically tells a user about the new command!

For an example: in my Leviathan bot I had a "guess my number" game in the commands folder: https://github.com/aichaos/graveyard/blob/master/Leviathan/commands/games/guess.pl

Or a fortune cookie command: https://github.com/aichaos/graveyard/blob/master/Leviathan/commands/funstuff/fortune.pl

After we saw Andromeda set the pattern for self-documenting commands like this, I applied it to my own bots; members on Bot-Depot would pick one bot program or another that they liked, and then the community around that program would write their own commands and put them up for download and users could easily download and drop the .pl file into the right folder and easily add the command to their own bots!

I think there was some effort to make a common interface for commands so they could be shared between types of chatbot programs, too; but this level of collaboration and innovation on Bot-Depot is something I've rarely seen anywhere else since then.

We had also gone on to apply that pattern to instant messenger interfaces and chatbot brains, as well - so, Leviathan had a "brains" folder which followed a similar pattern: it came with a lot of options for A.I. engine to power your bot's general responses with, including Chatbot::Alpha (the precursor to my RiveScript), Chatbot::Eliza (an implementation of the classic 1970s ELIZA bot), and a handful of other odds and ends - designed in a "pluggable", self-documenting way where somebody could contribute a new type of brain for Leviathan and users could just drop a .pl file into the right folder and use it immediately. Some of our bots had similar interfaces for the instant messengers (AIM, MSN, YMSG, etc.) - so if somebody wanted to add something new and esoteric, like a CyanChat client, they could do so in a way that it was easily shareable with other botmasters.

For more nostalgic reading, a long time ago I wrote a blog post about SmarterChild and other AOL chatbots from around this time. I was meaning to follow up with an article about MSN Messenger but had never gotten around to it!

0.0021s.